Childhood memories, especially those of a happy childhood, linger throughout one’s life and bring moments of much joy and contentment. My father who had such a fortunate childhood spent in his hometown of Jaffna, often shared his reminiscences with us, his three children. He wished to impress on us that the simple way of life with love, affection and understanding among the family members which he had experienced, was far superior to all the wealth in the world. He also wanted to emphasise that life was not all a bed-of-roses for him and that he had to work hard to achieve his ideals which made his life meaningful.

Childhood memories, especially those of a happy childhood, linger throughout one’s life and bring moments of much joy and contentment. My father who had such a fortunate childhood spent in his hometown of Jaffna, often shared his reminiscences with us, his three children. He wished to impress on us that the simple way of life with love, affection and understanding among the family members which he had experienced, was far superior to all the wealth in the world. He also wanted to emphasise that life was not all a bed-of-roses for him and that he had to work hard to achieve his ideals which made his life meaningful.

One of my father’s treasured memories of his early childhood was the happy atmosphere in his home at Mohideen Mosque Lane off Moor Street in Jaffna town. As was traditional and popular at that time the married daughters and their families lived with the parents, and this pattern was followed in my father’s family.

The head of the family was ‘Appa’ (Mohamed Sultan Abdul Cader) a pleasant old ‘gent’ who owned a shop selling a variety of goods. His wife ‘Ummamma’ (Sultan Abdul Cader Nachchia) we remember as a petite lady with twinkling eyes and a ready wit. Their two daughters, I was told, were totally different from each other in looks and character, the older one (Mohamed Meera Mohideen Nachchia), who was my grandmother, was said to have been tall and fair while the younger was smaller and not so fair. When the elder daughter married, she and her husband, a budding young Proctor (Sultan Mohideen Mohamed Aboobucker), lived with her parents, and continued to do so after their son, my father, was born on the 4th October, 1911.

Pampered

When my father was nine years old his mother passed away and changes took place in the household. His father re-married and went to live some distance away, but he regularly visited his son who continued to live with the grand-parents. Soon ‘Ummachchi’, (Meera Mohideen Nachchia) my father’s aunt, married and she, her husband (Mohamed Meerasahib Mohamed Ibrahim Sahib) and later their three children (Shahul Hameed, Sithy Kathija and Noorul Jezeema) became part of the household. However, there was no lack of affection towards my father, he was greatly pampered and therefore became a little self-willed. Any mischief or slight disobedience on his part was often excused and ‘Ummamma’ would emphatically state, ‘after all he is only a small boy without a mother!’

The house where my father spent his happy childhood he always remembered with great feeling. We would often talk of the yard spread with white sand kept spotlessly clean by Ummachchi. Around this was stone-paved verandah into which the surrounding rooms opened out. On our frequent visits to this house my father would never fail to show us the room where he was born. In the compound was the famous woodapple tree. I have never as yet tasted sweeter woodapples and we were informed that when my father was young, the fruits of this tree were never plucked, Ummachchi would wait until the ripe fruits dropped off the tree and then give them to her young nephew.

Recollections of a girl-cousin portray my father as having a strong personality who always had his own way and had others follow him. She related an incident which we found very entertaining. She said that in this home there was a large bed with a kind of railing similar to a baby’s cot. My father would shove his three cousins into it and shout, ‘I am the keeper and you are the animals in the zoo. Now do as I command you!’ He would wave a stick and order them to sit, stand, crawl or sleep. These cousins loved him and looked to him as their chosen leader and helped greatly to dispel any kind of loneliness felt by an only child. They called him ‘Ponnik Kakka’ (Golden brother).

The children who lived down Mohideen Mosque Lane played, learnt their lessons and prayed at the nearby mosque. The boys regularly attended prayers dressed in checked sarongs, white shirts and the distinctive white skull-cap. Much time was spent in religious instruction at the Allapichai Madrasa which later became the Muhammadiya Mixed School, and it was at this early stage that my father began to have a deep respect for religion, a respect he instilled into us.

In the cool evenings after a hard day at school and at the mosque, my father recollected how his cousins and he gathered with other children and played ‘catches’ and ‘hide-and-seek’. The lane was their playground. During the rainy seasons they had a wonderful time just running about in the rain and feeling the refreshing raindrops on their faces. The puddles that formed in the middle of the lane were grand to splash in and they had mock battles . The thick, slimy mud churned up by many passing feet was ideal to ‘down’ one’s enemy who was then covered with the sticky mud.

The rains also brought the ‘thumbi’ and these insects provided another form of amusement. The boys would try to catch them with a ‘thondu’ and then dissect them limb by limb. This sport was repulsive to my father and he shied away from it.

He also mentioned that the rainy season was the time when some type of worm known as ‘rathe’ appeared in plenty. They would be found curled up in dry corners inside the house. My father could not bear to see cooked prawns at table for he said that they reminded of those ugly worms.

My father was exceptionally fond of Ummachchi. He often spoke of what an expert she was in the culinary art. As she was also very fond of him she was ever willing to prepare any dish he wanted. His favourite food which he requested often was ‘paladai’. He described it to us as a kind of ‘roti’ made of rice-flour and coconut milk, but had to be thin and paper-like to be really tasty. According to him this simple meal of paladai together with Ummachchi’s tasty meat curry outdid all the elaborate dishes served at any famous hotel!

School Days

Recollections of school were as happy as those of home. My father began schooling in 1921 at Vaidyeshwara Vidyalayam and then proceeded to Jaffna Hindu College. He learnt his lessons in Tamil and did not learn a word of English until he was in Standard III. He remembered his teachers with great affection, appreciation and respect.

The grandfather was well-to-do and could have afforded to send his grandsons to school by buggy cart, but my father had to walk the one-and-half miles to and fro from school every day. This was indeed an enjoyable trip for all the boys walked together laughing and chatting.

One contemporary of my father recollected that these boys on their way to school was a sight worth seeing – there was Azeez in his typical Muslim attire complete with white skull-cap in the midst of his Hindu friends.

During his schooldays my father’s very close friends were Senathirajah and Subramaniam. Senathirajah, who joined the Income Tax Department later, and my father were lifelong friends. The Founder of Vaidyeshwara Vidyalaya T. Nagamuthu’s son Manicka Idaikkadar and my father were colleagues in the Ceylon Civil Service and close friends.

Having been a distinguished student and a respected old boy of the two Jaffna schools, my father was honoured to open the Diamond Jubilee Carnival at Jaffna Hindu College in 1951 and deliver the Golden Jubilee Address at Vaidyeshwara Vidyalayam in 1963.

On his days spent at Vaidyeshwara Vidyalayam my father has stated, “I now feel thrice-blessed that I did go to Vidyalaya and nowhere else. My period of stay, February 1921 to June 1923, though pretty short quantitatively was extremely long qualitatively. It was at Vidyalaya that I became first acquainted with the devotional hymns of exquisite beauty and exceeding piety for which Tamil is so famed through the ages and throughout the world.”

Regarding studies, owing to his early introduction to the Holy Quran, the importance of knowledge and education, which Islam advocates was deeply ingrained in him. It was his mother who was a strict disciplinarian, he would say, who first instilled the strong faith in Allah and the necessity of having a good education. He would remember her powerful voice relating stories of the Prophets to him. It was her encouragement that made it possible for him to read fluently works in Arabic-Tamil. Of an evening he recollected reading extracts from ‘Noor Masala’, Abbas Nadagam’ and ‘Seera Puranam’ in addition to extracts from the Holy Quran and the ‘Asma-ul-Husna’ the Ninety-nine Glorious Names of Allah. The grown-ups sat around and listened attentively.

‘Seek knowledge from cradle to grave’ (The sayings of Prophet Muhammad) and ‘Knowledge is Power’ (Bacon) were two of my father’s favourite quotations. He would tell us, ‘Intelligence is not enough to get you to pass exams, you must burn the midnight oil’. He would study late into the night with the aid of a flickering oil lamp, while Ummamma feeling concerned about him and wishing to keep company, sat nodding away in a corner.

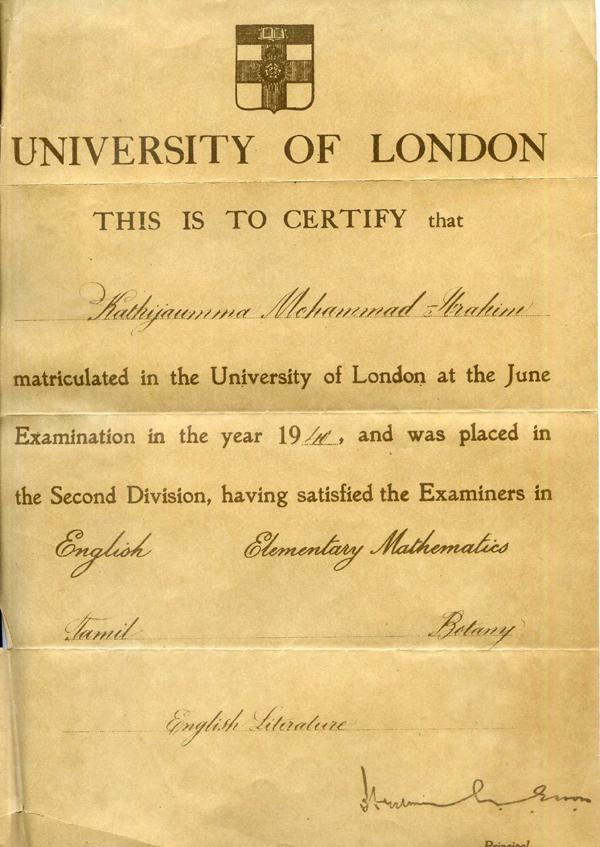

My father’s cousin, Sithy Kathija, mentioned how he made her promise that she would sit the London Matriculation exam. She had solemnly promised not fully aware of what it implied, for it was a time when Muslim girls did not attend school or at most studied only up to Standard III. She continued her studies at Vaidyeshwara Vidyalayam and later at Holy Family Convent, Jaffna. It must have indeed been a grand occasion for my father when this cousin did sit the exam and became one of the very first Muslim girls to pass.

Another amusing recollection, though not strictly a childhood one, concerns the marriage broker who began to plague my father during his student days, everytime he came to Jaffna for his holidays. They were of all types from old hags to ‘lebbes’ and distant relatives. They offered brides with handsome dowries. He would have nothing of this, so one day in order to stop them worrying him, he had stood on a table, danced a kind of jig and shouted, ‘Can the bride dance like this? If so I will marry her at once.’ The marriage brokers did not trouble him any more.

Although my father lived the greater part of his life in Colombo he never forgot Jaffna and the happy times he spent there. Nor did he forget the many teachers and friends of his childhood. Recollections of his childhood and his life in Jaffna had a special place in his heart and he wanted to share with us these happy memories. The Palmyrah palm at our house “Meadow Sweet” at Barnes Place in Colombo was a memorable symbol.

Reflecting on what my father told us about his happy childhood and early upbringing within a close-knit family, it appears that in later years his ideas on the necessity of education for the advancement and well-being of the community, the importance of female education, his deep respect for Islam and for other religions and his liberal views grew from these early days.

An Advocate of Women’s Rights to Education

As a scholar and educationist, much has been discussed, debated and written about my father’s education policies and his ideas for the advancement of Muslim education. However, nothing, or rather very little, is mentioned about what he felt about the education of Muslim girls and the much talked of status of Muslim women.

Having benefited from his ideas concerning these two themes, let me share a few thoughts – interesting because they were far, far advanced for those times.

The education of girls was something he was very interested in; even at a time when Muslim girls did not have any form of schooling. In the 1920s, he encouraged my aunt (his cousin) to sit her London Matriculation Examination. It was a happy day for him when she became the first Muslim girl in Jaffna (possibly in the whole island) to pass this exam. Needless to say I was also encouraged in the pursuit of knowledge.

To my father, reading was the first step towards gaining knowledge and he felt that the reading habit must be fostered among children from a very young age. My brothers and I were encouraged to read books, to buy those which we particularly liked and taught to look after books. I am ever grateful to him for instilling in me the love and respect for books and for the wonderful library of books that he helped me to collect.

At a time when Muslim girls, especially those of well-to-do families, stopped attending school when they attained age, my father would not hear of me staying at home and learning to sew and to cook. At this stage there was no problem – my mother was also keen to allow me to continue my schooling. The real problem arose when it was time to decide whether I should go to University. I must admit that my mother was in favour of a university education but was reluctant to encourage me because of what the family elders would have to say.

I was keen to follow a varsity career and thanks to my father’s insistence I was able to enter the University campus at Peradeniya.

When I was leaving home for the first time to follow this much desired varsity career, my father gave me a piece of advice which I will never forget. I should be happy with my studies; one should not think in terms of material benefits but read the subjects one liked and try to do one’s best.

My mother complemented these sentiments – she told me to enjoy myself and not to study too hard! I did just that and my years spent at the Peradeniya Campus were the happiest of my student life, especially because I was given the freedom to choose my friends and take part in campus activities.

Both my parents advised me not to become (in my words) an Intellectual Snob! I should not look down on those who were less educated than myself – in short, to keep my head. I should also learn those feminine arts of good home-making. Thus during the holidays I attended sewing classes, cookery and cake-decorating courses, which were my hobbies.

The time I entered my teens was one when the Purdah system was rigidly followed. Young girls led secluded lives until they were married off. I remember the married Muslim ladies wearing long black coats, often made of rich velvet, black head-dresses and black face-veil when they attended weddings and other functions, even the cars had curtained windows.

My father did not approve of this “purdah garb”. I remember my mother always in favour of compromise, wore the black coat but discarded the head-dress and merely covered her head with the saree. Many Muslim ladies in those days followed this style. As for me, I did not have to wear the coat or cover my face.

I may have broken this “Purdah” rule in the Muslim society of that time, but had to dress modestly and simply. No sleeveless blouses or short skirts for me. At a very young age I wore the Salwar/kameez, Punjabi, as it was termed then.

My parents had very definite ideas about the dowry system which was prevalent to a very high degree among the Muslims. This system, where the bride’s parents must give a dowry of cash, jewellery and property to the bridegroom before the marriage took place, is not mentioned in the Holy Quran or the Hadiths (Traditions). My parents disapproved of it. In fact, a statement made by my father stressing his views on the dowry system is recorded in Hansard of the late ‘50s. Fortunately for me, the young man I decided to marry came from a family who equally disapproved this system.

Islam gave women a rightful place in society; even today much discussion and argument takes place regarding the status of women in Islam. What my father said to me when we were leaving for Scotland where my husband was to read for his Ph.D. at St. Andrew’s University, comes vividly to my mind when I hear these discussions. He said that my place was not to compete academically or career-wise with my husband, but to help him to do well in his career, so much for Women’s Lib! Needless to say, this was the relationship that my parents had.

My mother may not have been academically qualified, but she stood alongside my father – she ran a beautiful home where anyone was welcome, entertained official guests, travelled to foreign countries with him – in short, she was the understanding companion that a wife, even a highly educated one, should be.

My parents instilled in me that one must live according to the teachings of Islam, however, they were broad-minded and did not over-do this. A favourite comment of my father was that we should live according to our religious traditions, but at the same time we must also understand and respect the religious and cultural traditions of other communities in this country. Maintaining a frog-in-the-well mentality would be disastrous.

Throughout the centuries the Muslims have contributed to the welfare of this country whilst upholding their religion and culture – in the future too they can work towards the prosperity of their country while preserving and maintaining their religious and age-old traditions.

(Marina started schooling at Carmel Girls’ English School, Kalmunai and St. Scholastica’s Convent, Kandy when her father served as AGA in Kalmunai and Kandy respectively. She completed her education at Ladies’ College, Colombo, graduated with Honours in Geography from the University of Ceylon in 1960 and obtained a M.Phil. from the Colombo University)

Sithy Kathija’s Certificate on passing the Matriculation Examination of the University of London in 1940 as the first Muslim girl.